]> Here are some issues licensors and licensees should consider before signing on the dotted line. Most of today's licensing agreements are based on the payme

April 6, 2018

]>

Here are some issues licensors and licensees should consider before signing on the dotted line.

Most of today's licensing agreements are based on the payment of a royalty to the licensor by the licensee. The royalty is a percentage based on a sales price of the goods (the wholesale price if the product is sold at wholesale and the retail price if it is sold at retail). This sounds simple, but numerous difficulties often arise in negotiating and interpreting royalty rates, primarily pertaining to the rate basis, payment timing, advances against royalties, guarantees, and auditing. It's vital for both licensors and licensees to be aware of the issues and understand how certain contractual provisions can affect their bottom lines.

Playing the Percentages

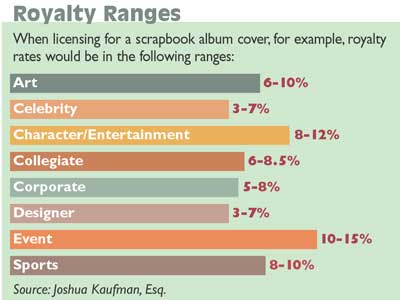

The actual royalty rate (the percentage number) is not usually a subject for debate. Each industry has developed certain parameters into which most deals fall. The type of licensed property, such as art, celebrity, collegiate, corporate, designer, character/entertainment, event, or sports, frequently determines the range of royalty rates (see chart).

On what are royalty percentages based? In general terms, the licensee (manufacturer) sells product into retail at wholesale (plus markup) price points. However, there are cases when the licensee is a direct-mail vendor and sells at retail or has two programs, one wholesale and one retail. If a royalty is based on receipts, then the licensor would anticipate and get a portion of the higher retail prices obtained by the licensee, right? Not necessarily. Licensees in their standard contracts often propose a royalty rate of only half the amount being offered on a wholesale sale when the sale is at retail. Effectively, even though the licensee is receiving twice as much for the licensed product, the licensor earns the exact same amount.

Another issue that arises frequently is: At what point in time is the royalty earned? It is in the licensor's interest that the royalties are earned upon the shipment of goods. Licensees, on the other hand, seek to pay the royalty to the licensor only upon receipt of payment from their retail customers. Thus, if royalties were due within 30 days from when the goods were shipped, versus when the licensee receives payment from its retail customers, it could make the difference in receipt of royalty payments for the licensor of a period of several months.

A much larger problem is whether royalties are due on goods shipped but not paid for by a licensee's customer. Of course, the licensee takes the view that it has already lost money by its customer's non-payment and shouldn't have to pay a royalty. On the flip side, the licensor feels it is entitled to be paid regardless of the receipt of payment by a licensee's customer. The reasons are twofold. First, once the licensed products enter the stream of commerce, the licensor has fulfilled its obligation. Second, the licensor does not want to be in the business of guaranteeing the credit of the licensee's customers. The licensor has no say as to whom the licensee sells to or whether it is choosing to take a credit risk, be aggressive in collection, etc. The licensor feels that since the licensee is receiving anywhere from 85 to 97 percent of the revenues, a sum should be put aside for uncollectibles.

Sum vs. Parts

Another factor in royalty rates is whether they will be paid on the gross or net figures. Few contracts pay on "gross." There is no magic or standard format for figuring out what the "net" should be. Certain sums traditionally are subtracted from grosses such as returns and shipping/ handling (when the customer pays a separate fee for the shipping and handling, but the payment is incorporated in the overall payment). After these two fairly standard deductions, all others are up for negotiation. It is in the licensor's interest to have as few deductions as possible, although licensees may come up with new items they want to claim as non-compensatable and not part of the royalty basis. This issue can be very problematic when a licensed product is bundled with other products. Licensors may request the royalty be based on the total bundled item price, not on the portion attributed to the licensed product alone.

For example, in art licensing, it is always a contentious negotiating point when the licensed product is the print, but the licensee sells the print matted and framed. Is the royalty to be based on the total matted and framed price or just the print's value? Most art licensors will argue the royalty should be based on the total package. Licensees argue with equal conviction the royalty should be based only on the pro-rata value of the print.

A point of growing dispute is Free on Board (FOB)-based royalties, particularly with imported goods. As more and more licensees are taking possession of their goods in foreign ports, they are trying to peg the royalty rate on the cost of the goods once they are on the ship in the foreign port, FOB. There can be a great difference in the royalties. The wholesale price is the price the licensee sells to the retail stores, while the FOB cost includes getting the goods on the ship bound for the U.S. (e.g., what they have paid the factory for the goods, the cost of getting it from the factory to the ship, packaging, container costs, export duties, and taxes). The difference between the two pricing systems is the licensee's profits and the additional costs built into the wholesale price from the time the licensed products are shipped from the Far East, for example, until they are delivered to a licensee's customers. These differences can be substantial. If the royalty is not adjusted upward for an FOB transaction, the actual royalty being paid to the licensor (if based on the same percentage point such as 6 percent) is significantly less than the standard wholesale royalty. There is no universal answer for what multiple should be used to equalize the differential, so the licensor does not lose money by having the rate pegged at FOB. The most common solution is probably to multiply the wholesale royalty rate by three; however, that is certainly not universal. Licensors can and should, in the course of negotiations, find out the wholesale price and the FOB price, and do the mathematical calculations so the net royalty numbers come out roughly the same.

Advancing the Cause

Two related issues regarding royalties revolve around advances against royalties and guaranteed royalties. An advance is generally a non-refundable fee paid up front upon the signing of the contract (it also can be made annually or as part of any renewal period), in which the licensee pays the licensor a sum in anticipation of future royalty receipts. The licensor does not receive any more payments until the licensee has fully recouped its advance. For example, if the royalty is to be a dollar per unit, and an advance of $10,000 has been paid, the licensor will not receive any additional royalty payments until 10,001 of the licensed products have been sold.

Guarantees work differently. Instead of looking to the front end of the transaction, one looks either to the end of each year of the transaction or until the end of the initial term of the agreement. The parties then add up how much has been paid to the licensor. If they have not reached the guaranteed amount, the licensee must come up with a lump sum payment to make up the difference. For example, if the guarantee on a contract was $100,000, but at the end of the year or contract term the licensor only earned $90,000, the licensee owes a $10,000 lump sum to reach the level of the guarantee. Depending on the nature of the arrangement, guarantees can be monthly, quarterly, annual, or simply for the whole term of the contract.

Licensees often will attempt to lower the amount of an advance claiming that at the start of the relationship, they want to have their funds available for product development, marketing, and advertising for a new product. The more a licensee pays the licensor up front as an advance, the more it drains from the project. Licensors prefer to see as much money as they can up front to ensure the transaction is worth their while and as an incentive to the licensee to push their product. The same holds true with the guarantee: The larger the guarantee, the more incentive the licensee has to push the product. However, since the guarantee usually is paid later in the contract term, it provides the licensee the ability to expend funds on product development and promotion.

From a licensor's point of view, advances and guarantees are imperative when dealing with exclusive contracts. A licensee can have many product lines. If one is not working out or the person behind the product leaves, the licensee can, and often does have other products it can push to make up for any shortfall in the sale of the licensor's product. On the other hand, the licensor frequently has one product or a limited line. If it has signed an exclusive contract with the licensee and the licensee is not performing, the licensor is sunk without a large advance or a substantial guarantee because of the exclusive nature of the contract. It is precluded from going elsewhere, yet not earning any money with a licensee that is not selling its goods. It is very dangerous for a licensor to enter into any kind of exclusive agreement without a sufficient guarantee to offset the risk.

Audit clauses are another vital term in every licensing arrangement based on royalties. With every royalty check or period, even if no money is due as a result of advances, the licensee provides the licensor with product sales information. If at any point the licensor believes the information it is getting is inaccurate, it will need to have a right of audit to inspect its licensee's books. The frequency of royalty audits, who pays for the audits, what copies can be made, confidentiality agreements, and other terms and conditions are points of negotiation in the contract.

You May Also Like