Since the days of the Silk Road, China has played a central, often defining role in world commerce. Now, through a combination of political and economic forces, that role is evolving.

December 13, 2018

China is one of the most prolific civilizations in the history of the world, with a record of creativity and enterprise that spans three millennia. And while there's no doubt that much has changed over that time, those changes might not be as dramatic as they first seem.

The Great Wall of China dates back to the 7th Century BC, but just this year, China completed the world's longest sea bridge.

And what is the Internet but a modern Silk Road, serving as a conduit for commercial and cultural exchange around the globe? Viewed in that context, China's role as the world's largest exporter (and second largest importer) seems natural and its growing economic and technological influence inevitable.

Over the last three decades, China's economy and position on the world stage has undergone a massive transformation, spurred by landmark policy reforms in 1978 that began to reverse the country's long-standing economic isolation.

Now, China's economy is the second-largest in the world and one of the fastest-growing, despite a recent slowdown in the pace of that growth.

And yet China's relationship with the world continues to be muddled by the complex interplay of its historical sensitivities, communist political ideologies and capitalist economic ambitions.

From Producers to Consumers

One thing is clear though, and that is the rapid economic evolution that is taking place across the country. Wages are rising and the middle class is growing, as is disposable income. This in turn has led to massive increases in consumption, driving growth not only in China, but the world. The International Monetary Fund predicts that the world economy will grow by 3.9 percent this year, and China will account for a whopping one-third of that growth.

Increases in wages in China have made manufacturing, historically the country’s economic backbone, more expensive. As a result, some manufacturing business is moving to lower-wage countries like Vietnam and Malaysia, but those losses are being offset by increases in domestic spending. In fact, domestic consumption contributed to 77.8 percent of China’s economic growth in the first quarter of this year, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics. This represents a huge shift in the fundamental character of the Chinese economy–from low-cost production hub to consumer market.

China’s leaders welcome, in fact sought, this change, but that doesn’t mean they’re giving up on manufacturing altogether. Quite the opposite, in fact. In 2015, the government launched Made in China 2025, a 10-year initiative aimed at upgrading the country’s advanced manufacturing capabilities to reduce reliance on foreign technology and shift industrial efforts toward higher value sectors like AI, robotics and bio-medicine.

All’s Fair in Trade and War

The announcement inflamed tensions with governments around the world, in particular the U.S., offering a new focal point for Western ire over China’s insular trade practices and ineffectual efforts to reign in IP infringement.

These issues are some of the same tinder fueling the ongoing U.S./China trade war, which continues to ratchet up in intensity. In the face of increasing international hostility, President Xi Jinping has made several calls for China to become more “self-reliant,” and doubled down on the Made in China 2025 initiative.

Ironically, this nationalistic, reclusive instinct has its roots in another trade dispute–the Opium Wars with the British Empire in the 19th century, which weakened the previously dominant Chinese economy and led to the period known as the Century of Humiliation. These deep-seated historical wounds still echo in the Chinese ethos today.

“Like an adult who was bullied in grade school, China continues to bristle at anything that even hints that others are pushing it around,” says Bryan Van Norden in a commentary for the public policy think tank The National Interest.

The Chinese stock market and the valuation of the yuan have taken hits in recent months, due in part to trade tensions, as well as the slowing growth trend. The IMF lowered its 2019 growth forecast for China to 6.2 percent (down from the original estimate of 6.4 percent), but most analysts agree that this slowdown is primarily a sign of the market maturing. And at 6.2 percent China’s growth will still far outpace that of the U.S. (estimated by the IMF to be 2.7 percent in 2019) and the Eurozone (1.9 percent).

China GDP Growth (1978-2018)

Little Emperors

However heated world leaders get, it seems to be having a nominal impact on sentiment on the ground, which Tani Wong, managing director, The International Licensing Industry Merchandisers’ Association (LIMA) China, describes as “optimistic.” As fortunes rise, spending is increasingly shifting from necessities to discretionary categories.

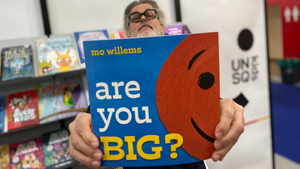

“With the rapid growth of the economy, Chinese consumers’ material needs are now being satisfied. As a result, consumer demand is moving more to the emotional,” says Amy Xiao, project manager, Informa/UBM, which organizes the annual trade show Licensing Expo China.

Indeed, as China’s role on the world stage changes from producer to consumer, Chinese consumers’ mentality is changing accordingly. These tech-savvy shoppers are increasingly sophisticated in their demands, looking for quality and personalization.

As in other world markets, much of this new demand is being driven by the country’s younger consumers, but in China, this demographic has a unique profile shaped in part by the One-Child Policy (which lasted from 1979-2015). Forty-one percent of the current Chinese population is aged 10-39, according to data from the United Nations, and most of them were born under the One-Child Policy. In many cases these children were raised to be the sole focus of the family and have been encouraged to take advantage of the benefits of improved economic conditions that their parents were denied.

They are known as the Little Emperors, and, in short, they are natural-born consumers.

The Era of ‘New Retail’

The Chinese consumer in general, and the Little Emperor subset in particular, is known for being an eager, early adopter of new technology and trends, which has helped China become a dominant force in shaping the future of retail.

Two years ago, China surpassed the U.S. as the largest retail market in the world. The country now accounts for 42 percent of all global e-commerce, according to the World Economic Forum, and Singles’ Day every Nov. 11 is the largest shopping day in the world. (These numbers are particularly remarkable when you consider that a decade ago, China’s e-commerce share was 1 percent.)

“Scale makes the China opportunity strategically significant, but it is retail innovation that truly puts it in a category of one,” says Michael Cheng, Asia Pacific & Hong Kong/China consumer markets leader, PwC, in the report “China’s Next Retail Disruption.”

Leading the charge is the world’s largest retailer, Alibaba. Online sales penetration in China is the highest in the world (source: Statista), but Alibaba says that, by its account, more than 80 percent of total retail sales still come from brick-and-mortar. Which is why, in 2016, Alibaba founder and executive chairman Jack Ma announced plans for what he calls “New Retail.”

“The possibilities for New Retail are endless once you erase the lines between online and offline and reimagine it based on the way consumers actually want to shop,” touts a company video promoting the concept. “The key to saving traditional retail is to forget about tradition altogether.”

This year, e-commerce sales in China are predicted to reach $1.53 trillion, and Alibaba’s online marketplaces Taobao and Tmall will account for 58.2 percent of that, according to eMarketer.

Knowing that, it could seem bold for this e-commerce behemoth to position itself as the savior of brick-and-mortar. And yet, it’s working.

Case in point, the company’s new-age Freshippo supermarkets (formerly called Hema), which serve as brick-and-mortar testing grounds for the New Retail concept–app-enabled barcodes not only tell you the price of a product, but also nutritional and sourcing information; stores double as distribution centers, making 30-minute delivery of online orders the norm; in-store restaurants prepare the food you just bought; a digital record of previous purchases makes it simple to reorder; and only mobile payments are accepted.

Not only has Freshippo revolutionized what has been described as a “primeval” grocery retail scene in China, the concept is reimagining brick-and-mortar retail as a whole. Sixty-five Freshippo stores are already open across the country, and Alibaba plans to open 1,000 more over the next five years. China GDP Growth (1978-2018) And Freshippo is just the beginning. Here are a few of Alibaba’s other retail innovations, ranging from reboots of entire industries to subtle product enhancements:

Try” before you buy: “Magic” mirrors integrated in beauty shops and mall powder rooms use augmented reality to allow shoppers to “try on” makeup.

A new kind of home shopping network: Merchants can now live-stream on the Taobao marketplace.

Car vending machines: Customers browse cars in an app, then pick up the one they want from an unmanned vending machine and test drive it for up to three days.

More convenient convenience stores: The Ling Shou Tong program helps local convenience stores modernize with new interior design and a custom-built app that digitizes inventory management.

Powered-up products: Alibaba amped up a partnership between Fantawild Animation’s “Boonie Bears” and Master Kong water by adding AR integration on each bottle.

Virtual shelves: Shoppers who don’t find what they want in-store can select the product they want on a nearby screen and have it delivered.

Augmenting Starbucks: The Starbucks Reserve Roastery in Shanghai integrates with Alibaba’s Taobao app for in-store activations powered by AR.

There is one common denominator across almost all of these concepts–the mobile phone. And with the largest population of smartphone users in the world (more than 775 million, according to Newzoo), China is a fertile mobile retail testing ground.

“In China, a smartphone helps us settle almost all transactions,” says Wong. “Recently, we have unmanned supermarkets, convenience stores and bookstores where you use your smartphone to enter the shop and check out.”

In fact, according to a recent PwC report, “mCommerce and mPayments are no longer trends; they are ubiquitous characteristics of retail in China.”

'A Trademark of China’

At the Shanghai International Import Expo in November, President Jinping said China would “continue to broaden market access,” adding that “openness is a trademark of China.”

But while the benefits of doing business in China are clear, for many brand owners there remains one overriding concern–IP protection.

Opinions are divided on how much progress is being made on this front. President Jinping frequently touts his country’s resolve to protect foreign IP, and yet just this October, the U.S. Justice Department charged 10 Chinese nationals (several of whom are alleged to be government agents) with conspiring to steal aviation technology.

China is making efforts to tackle counterfeiting with some success, including a series of new trademark laws and the institution of an annual crackdown on online infringement called Jianwang. In April, President Jinping announced that he was reinstituting the State Intellectual Property Office to step up law enforcement efforts.

“The situation [with counterfeiting] is improving gradually, and as the country gets more affluent, both retailers and consumers have become more brand-conscious,” says Wong. “Also, online retailers like Alibaba and JD.com have set up separate business divisions to handle licensed products.”

Wong advises foreign business owners to enlist the help of local professionals who understand the intricacies of the Chinese market.

“Do your homework and trademark your brands for key categories first before entering the market,” she says.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like