]> BBC Worldwide's publication of guidelines concerning the use of its characters in food products marks the entrance of the licensing industry into the debate about the link betwe

April 6, 2018

]>

BBC Worldwide's publication of guidelines concerning the use of its characters in food products marks the entrance of the licensing industry into the debate about the link between character licensed food and unhealthy eating in children, which is raging at the moment in the UK. Sam Phillips asks how stewed up should we be about it?

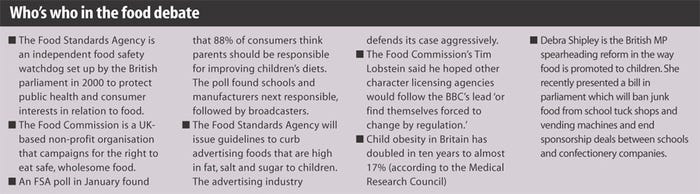

It's easy to feel fed up with reading about the problems of childhood obesity in the press. There are alarming figures about the increase in early-onset diabetes, warnings that we may outlive our children and projections for how much this is all going to cost the health industry in the future. Implicit in the debate is the notion that pester power is at fault. And implicated in that are greedy entertainment companies forcing children to pester for unhealthy food by making it irresistable to them. If you add the pros and cons of advertising food to children into the equation you have a complex and emotive debate.

The notion that character licensed food makes children overweight is simplistic. As is the notion that it is entertainment companies that decide what children eat. However, there is enough evidence on the table now to show that obesity in children is a national concern requiring positive action. Our industry gives licences to food companies to put characters onto food that is attractive (and often advertised) to children. We cannot claim to be ignorant, when signing a licence, about the nature and ingredients of that food product. One food industry insider told me only the very big licensors ever ask him about a product's ingredients.

We know why food companies need licences: they give a product 'standout' in a crowded supermarket aisle. We know that children like food that is high in salt, fat and sugar, (the three deadly sins in children's food) and will pester for it again. We know that this debate is not going to go away. Which is why it seems a good time to write about it now. As an industry we need clear opinions and strategies to contribute to the debate, because it will continue to rage in the media and in the supermarket aisles until governments start suggesting their own rules about it. Whatever the counter arguments, a generation of overweight and unhealthy children is something that affects us all.

So where does the licensing industry fit into all this? It is implicated because it creates the hype and fashion for a particular character, which then becomes associated with food, which is often advertised heavily on TV. Why should a child remember to eat an apple when they have watched an hour of TV containing adverts for far more delicious things? Why should a child know that the character yoghurts are only half as healthy as the supermarket ones? Many of the counter arguments to all this are well oiled, such as these comments from licensors: 'You can't add value to an apple by putting a character on it'; 'It's horses for courses; our business is about entertainment and fun' and 'It's up to parents to be responsible for what their kids eat'.

These are fair comments, up to a point. It seems reasonable that children taken out to the cinema for a treat can continue the experience afterwards by meeting their hero in a fast food restaurant kids meal. Scooby Doo, for example, is all about snacks. The irreverance and humour associated with boys' action shows or girls fashion brands are perfectly matched to the sociable experience of snacking, breakfasting, sharing packed lunches. For licensors, however, there is also a serious commerical justification for it. Food licences return healthy royalties (think up to seven figures per annum for a top canned pasta deal, for example) and provide awareness on millions of packages. The income received from 11 million Quick Service Restaurant Kids Meals being sold over just a couple of months is as irresistible to a licensor as the Kids Meal is to the child.

In the pre-school market things are more emotive. Any-one with a toddler will tell you that food can be a battle ground and that pre-school TV characters are role models. Combining food and role models can therefore be very potent. It's here that most of the bad press has been directed and the BBC has been the whipping boy for much of it.

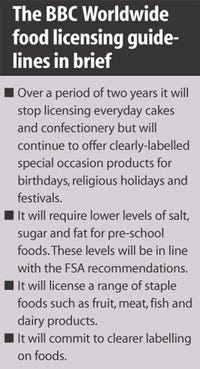

Which is why BBC Worldwide is first out of the gate with self-imposed guidelines about the use of its characters in food products. Its first major decision regarding food was to stop its characters featuring in fast food promotions in June 2003. At that time it decided more significant action was necessary and embarked on extensive research among 1000 consumers as well as reviewing all existing food licences with a nutritionist. Head of children's operations Helen McAleer explains the principal findings, 'Not surprisingly, we found that a high percentage of people look to the BBC for advice. We found, for example, that the nature of treats has changed and that there is confusion about labelling. We felt that if things were changing, BBC Worldwide must go first.' Worldwide drafted its internal policy and then consulted with The Food Commission and the Food Standards Agency, which then included the BBC guidelines in its full recommendations concerning promoting food to children. 'Communicating with these groups will hopefully mean consistency in the long term,' says Helen. The research threw up some interesing conundrums. Anecdotal evidence isn't necessarily supported by scientific links in the case of things like additives. Guidelines for the fat and sugar content of children's food are vague and apply to the very broad category of children aged 2-19. But Worldwide felt it was important to address all these issues. 'The BBC is just a small part of the whole debate. We have no control over the rights we don't own but this is the first step of a long-term cultural change,' Helen says.

How will it affect income? Food is worth approximately £1m per year to BBC Worldwide, with confectionery an important part of that. Everyday confectionery licences will fade out, but other food categories will come into play. There are considerations for retailers, too. For example, in offering a single celebration cake that clearly states it uses only natural colouring, amongst a larger selection that don't. It's colours will also be very muted in comparison. The good news is that we can expect the food manufacturing giants involved with character licensing to make appropriate changes to ingredients and labelling quite soon.

Bon Bon Buddies, the market leader for kids character biscuits for example, takes concerns about healthy eating seriously. Most of its products are packed in portion contolled packs and offer significant play value with play or learning features included. Bon Bon is responding to the FSA consultation to present the character biscuit market in a positive light. It will also continue to make it easy for parents to understand its products and supervise their children's consumption. It also adds the balanced view that, 'Part of the pleasure of being a child is enjoying a favourite TV or movie character through play and everyday life. Good quality food products with real character synergy, portion control and added value must continue.'

There are some very healthy licensed food products on the market. Sunmark has created a Mr Men organic fruit range; water company Font Vella has licensed Hamtaro onto its bottles in Italy and Looney Tunes have also been used to sell water. A line of Roald Dahl organic fruit juices will soon be launched. In the UK, Buxton Foods launched its award-winning range of Peter Rabbit organic food for young children last year with a six-month exclusive in Waitrose. At first glance, it's a premium brand, but the line has now been listed by Tesco (for which Buxton has developed a new roast courgette pasta sauce) and Safeways and has found no resistance to the prices being at the higher end of the scale. 'The feedback from buyers is that parents want to buy the best for toddlers,' says Buxton's Katie Towers. Buxton is developing new sauces for this summer, together with chilled items and products suitable for lunch boxes. Katie re-iterates, 'You don't need sugar and salt to make it taste good.'

The UK Football Association (FA) has put together a clear brief for its licensing into food categories in association with its agent CPLG. At the moment a celebration cake and chocolate biscuits exist but the next stage of licensing will utilise the FA's power to communicate positive messages and to encourage healthy eating to be cool. 'It's logical. The FA is associated with sport, so it shouldn't have a licensing programme held up by sugary or fatty foods,' says CPLG's Andrew Carly. The FA would also like to use its packaging to deliver a nutritional message and also a healthy lifestyle message, about playing better football and doing better at school. Andrew hopes the credibility of the FA could turn pester power into a welcome thing.

What next?

BBC Worldwide continues its hunt for new food categories to license into and companies like Buxton Foods will expand its range. Statutary guidelines about the salt content of children's food will come from the EU next year. As we've already said, this isn't a debate just about licensed food. It is, more importantly, about exercise, lifestyle, the domination of supermarkets, the difficulty in accessing fresh food outside working hours, about education and role models. There will always be chocolate and biscuits and sweets and unhealthy, delicious food. But there must also be a proactive licensing industry response to public opinion that sees red in the confectionery aisles. We can't wait for children to take the lead. But we can start looking for revenue streams in activity and healthly food and we can learn to make those products irresistible to children.

You May Also Like