]> Major food companies are cooking up licensing deals to extend their brands into non-edible categories. Food licensin

April 6, 2018

]>

Major food companies are cooking up licensing deals to extend their brands into non-edible categories.

Food licensing-often quiet, sometimes plodding, almost always strategy-conscious-is arguably the most evergreen segment of all the brand sectors in the licensing business. Beginning this year, it's going to get much more boisterous.

Food brands, those billion-dollar supermarket shelf staples, are upticking their interest in licensing. Several are hiring agents to explore new categories, signaling changes are afoot in how food-based licensing deals are brokered. From expanding into cookware and snowboards to declining lottery ticket extensions, here's how the biggest food players are selecting categories and partners to help bolster their brand presence and consumer recognition.

Campbell's Expansion

The $2 billion Campbell Soup brand, with a 100-year-plus heritage and a pop art icon connection via Andy Warhol, sees a great deal of opportunity in kitchen activity-related licensing and beyond.

Cookware is the latest extension from the soup company that cites warmth, nutrition, and comfort as some of its leading brand attributes. Cookware seemed a natural tack, as soups are the fourth or fifth most common recipe ingredient, says Lynne Chappel, director, corporate licensing, of the Camden, NJ-based brand. Retail sales of licensed Campbell Soup-inspired goods are about $35 million currently.

Items such as the steep-sided 10-inch sautðan and the five-and-half-quart soup pot are designed to accommodate the current popularity of simple, one-step/one-pot dishes. Cookbooks and a bonus recipe/coupon booklet may be in-packed in the $29-to-$50 seven-piece collections. The mass and supermarket tiers are targeted.

A. Aronson produces the Campbell's cookware; for years it has made plastic food storage containers for the likes of Campbell's, General Mills, Nabisco/Kraft, Kellogg's, and now Master Foods USA (formerly M&M/Mars). President Bruce Aronson's background in buying cookware for a department store chain is one reason the plasticware resource landed the deal.

Cookware joins Campbell's other kitchen components such as appliances from Select Brands, tools and gadgets from Marco Home Products, cookbooks from Publications Int'l., melamine from Trudeau Corp., and kitchen textiles from Franco Manufacturing. General Mills' Betty Crocker carries similar components, plus baking-centric extensions such as cake decorating kits, resulting in an $85 million licensed goods retail empire.

Campbell's also seeks to build its brand in the family area. The "Campbell Kids in the Kitchen" concept encompasses family cooking kits, with room for both real food and play food interpretations; trains and vehicles; arts and crafts; and toys and games based on the fun stuff floating in the soups (such as alphabet letters). This strategy is led by agency Lisa Marks & Associates in Rye Brook, NY, which Campbell's hired in October. Marks' family products expertise stems from building licensing and marketing programs for brands such as Disney, Nickelodeon, and publisher Penguin.

Outside the kitchen, Marks is focused on outdoor snow sports equipment, pajamas, and other forms of apparel that offer comfort and warmth, hence tying back into Campbell's brand attributes.

Brand Discernment

Because food brands generally represent wholesomeness and nourishment, there are certain category extensions many brands won't consider, no matter how smart a match.

One agent tells the story of how a state lottery association proposed a tie-in of the food's icon-a happy, cuddly character-with an upcoming holiday lottery promotion. The agent, although cognizant that lottery revenue often funds public education programs, couldn't expose the family targeted brand to gambling.

"We always want to stay relevant to the brand's core attributes," says General Mills Manager of trademark licensing Leigh Ann Schwarzkopf, who, in addition to Betty Crocker, brokers deals for Wheaties, Cheerios, and several other cereal brands. "It's not always easy to decline a great idea, but if it doesn't fit with our brand's positioning, we have to pass." Schwarzkopf recently had to say no to an idea for some great animated characters for a Wheaties box collectibles program due to the fact that according to the Wheaties philosophy, only living (or once living) athletic heroes can grace those boxes.

New Faces

Long-term relationships are common and almost expected in the food category. Food licensees expect or are at least accustomed to a slow and steady growth rate as opposed to the fast up-and-down swings common with entertainment brands; many of these licensees work with several corporate brands. Aronson is one example, but Trudeau Corp. and glassware maker Shadle Enterprises also represent multibillion dollar corporate brand licensors.

Corporate brands tend to keep their licensing teams small, internal, salaried, and often commission free. Several big brands, however, have begun seeking additional help from agents, who are paid on a commission-like basis. Some industry observers worry that outsourced agents may compromise the integrity of the strategy-embedded brands, but Campbell's Chappel strongly disagrees.

"We don't currently have the staff we need to pursue all the opportunities [presented to us]," she explains, "and Lisa Marks was a great fit because she understands brand development from her Disney experience and has strong retailer and licensing relationships."

Kellogg Co., the Battle Creek, MI-based food giant, just announced that San Diego-based agency Equity Management Inc. will handle three Kellogg's breakfast brands: waffle brand Eggo, cereal brand Special K, and pastry producer Pop-Tarts. EMI's current roster of clients includes General Motors, Jack Daniel's, and Maytag.

"We have so many brands that cover different marketing segments, from children to adults," says Elisa Webb, Kellogg's director, worldwide licensing, "that the best way to support and research them appropriately is to hire a well-respected agency that knows food and licensing." After two years on the licensing scene, Kellogg's has amassed a $65 million retail sales presence and continues to license out characters such as Tony the Tiger.

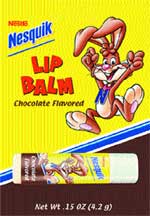

Swiss food behemoth Nestlé quietly hired Licensing Management International, based in Mission Viejo, CA, about a year-and-a-half ago to assemble a licensing program for the Nesquik Bunny. Today, about 10 licensees are on board, including Fromm Toys for milkshake makers and chocolate-flavored lip balm, Logotel for apparel, American Greetings for ornaments, and ODM for bobbing head toys, says Jim Rippin, managing director, LMI.

For about a year, Hershey Foods in Hershey, PA, has sought the assistance of Los Angeles-based consultant Siren Marketing to source licensees for non-food categories such as Christmas ornaments and social expressions. And just last month, Duncan Hines, the 50-year-old cake brand owned by St. Louis-based Aurora Foods, hired agency Global Icons to break into categories including bakeware and cookware, publishing, toys, and food-related product.

With more agents and consultants representing the big food companies, the ultimate benefits may be easier access to the grand brands, a more sophisticated choice of licensees, and a stronger momentum in sales volume and shelf space for the segment. The trick for food licensors is leveraging those benefits without surrendering brand control. After all, a slow and steady, strategic approach to growth is why these billion-dollar brands have lasted for half a century and more.

You May Also Like