]> Think it's easy and cheap to license a ringtone or wallpaper? Think again—there are lots of legal issues to consider first. Pick up

April 6, 2018

]>

Think it's easy and cheap to license a ringtone or wallpaper? Think again—there are lots of legal issues to consider first.

Pick up a newspaper, magazine, or trade journal, and you probably will find an article on wireless licensing. Today's cell phones are much more than just phones as they now boast broadband, hard drives, and GPS. As a result, it seems each week a new product or service is trying to port itself over to wireless. With these communication devices opening up vast new arenas for licensing, the question is: Are wireless deals different from traditional ones?

The answer is: Yes and no. Wireless agreements are similar to traditional licensing, but since this is a new industry, the structure of the deals is still in flux, and deals tend to have shorter terms and narrower territories and rights. Hard and fast guidelines do not exist and may never exist since mobile technology is constantly changing and the deals involved likewise always will be evolving. That said, several legal considerations must be addressed in any wireless deal, particularly those involving music and visual images.

Audio Feedback

One of the earliest and most popular types of wireless licensing comes in the form of music licensing for ringtones (what you hear when your phone rings), ring backs (what your caller hears if you do not answer), and true tones (when the original song is used). Any time music is licensed, a complex set of rights clearance issues arises. For example, first there is the individual(s) who owns the copyrights in the underlying song itself. Music and lyrics may be owned by the same person or two or more people separately (one owns the lyrics and another owns the music) or it could be jointly owned (where the writer and lyricist own the whole song together). When there is any use of the song—when it is recorded on an album, played on the radio or television, used in a jingle, used as a soundtrack, if somebody covers the song on a subsequent CD, or any wireless use—the owner is entitled to compensation. The writer(s) almost always has an agent who is known as a "publisher" in the music field. The publisher and the artist in a traditional deal split the royalties 50/50, although a successful artist might negotiate a better percentage.

That is only the beginning. Under copyright law, when a song is "publicly performed," a license is required. With wireless, the question is whether playing part of a song as a ringtone or ring back is a "public performance," subjecting the person offering the ringtone to the obligation of paying a public performance royalty. Songwriters, their publishers, and the companies they have delegated to monitor public performances and to collect fees for them (they are known as Performing Rights Societies such as ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC) all have taken the position that such uses are public performances and demand payment.

Next, copyright law provides for a separate license ("Mechanical License") when somebody is going to cover a song on his or her own CD and sets a statutory royalty rate. When a song is downloaded as a ringtone or ring back, it is considered a reproduction that requires the payment of a "Mechanical License." This generally is paid to an organization called the "Harry Fox Agency."

Complicated enough? It does not end there. If the actual sound recording is played as the ringtone or ring back rather than a new version created especially for the phone, then the record company must be compensated, as well, and a separate royalty negotiated with it. Surprisingly, licensing a 30-second segment of a song costs more than licensing the whole song. That's because in a standard record deal, licensing a segment is considered a "license," and the record company has to pay the recording artist 50 percent of the royalty. But allowing the use of a whole song is considered the "sale" of a single, and the royalty paid to the recording artist is only about 12 percent.

Finally, recording performers and record companies receive money when there is a non-interactive digital performance such as Internet radio or XM Satellite radio. So there might be a future situation (i.e., streaming music directly onto a cell phone) where a digital performance payment to the performers comes into play, as well.

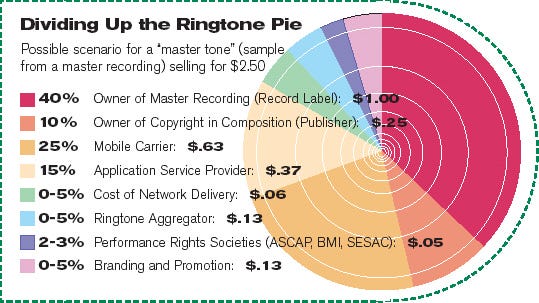

To get an idea of the royalties paid on an average ringtone that sells for $2.50, see the chart and figures prepared by Steve Masur, Esq., of Masur & Associates, LLC, a New York firm that extensively deals in ringtone licensing.

Optical Illusions

When it comes to the licensing of visual images (e.g., wallpaper and animations), the market is also new and the deals non-standard but generally not as complicated as music agreements. In the last year, I have negotiated deals where the royalties paid to visual artists or their publishers or agents (depending on who has the rights) range from a low of 5 percent to a high of 50 percent. This compares with traditional art licensing agreements in which most products are licensed in the 5 to 8 percent range with paper goods and prints in the 8 to 15 percent range. As time goes on, this industry probably will settle into regular norms but not necessarily the same as deals past since there should be lower production costs (for example, there are no tangible products or prints to manufacture). Such costs represent a large part of the licensee's expenditures, which, in turn, allows it to receive the lion's share of the proceeds. Without hard production costs for actual products, a 93/7 percent licensee-licensor split might be hard to justify. I anticipate a higher artist royalty will evolve in this area.

Royalties & Clauses

Related topics when dealing with royalties are advances and guarantees. However, the size of those, as in all parts of licensing, depends on the potential of the revenue stream as viewed by the parties. The higher the revenue potential anticipated by the parties, the higher the advance and/or guarantee. Therefore, in the wireless licensing deals I have encountered, the advances and guarantees span a wide spectrum, from a few hundred dollars to hundreds of thousands of dollars. That's because they are being based on a lot more guess work than extensive track records.

One of the trickier aspects in determining royalties is ascertaining how they are going to be calculated and allocated. Problems arise when royalties are based on bundled products and ad revenues. For example, a user subscribes to a news product in which he or she gets current events, sports, and entertainment news all for one fixed price, but there are separate providers for each of the components. If you are the provider of the news segment, for example, how are you sure the various allocations of revenue accurately reflect the value of your contribution? How are they tracked? How is the pro-ration being made? How are ad revenues being divided? What if ads are added to the platform after the agreement has been signed, but the deal was based only on a subscription-based fee-splitting model? How do you account for promotions, free minutes, and barters between the aggregator and deck provider? How is all this going to show (if at all) on your royalty statement? All these questions make the audit clause provided for in the license agreement all the more vital. The audit clause should give licensors access to meaningful documents, not just licensee-produced summaries. The auditor needs facilities with copying capability and knowledgeable personnel on hand to answer questions.

Another useful inclusion in wireless agreements is the "Most Favored Nation" (MFN) clause. When the first Internet and software deals were struck, companies made best guesses as to royalty rates, but each party knew the playing field was constantly shifting. Parties with clout demanded an MFN, meaning they agreed to a certain royalty rate, advance, or guarantee, but inserted a clause that if the licensee (or licensor) subsequently offered a better deal on a comparable license to a different party, then the agreement was adjusted to match that deal. Using MFN clauses provides participants with a degree of security that in entering into an agreement in a new area, they will not later feel they underpaid or overpaid. It also allows more flexibility in compromising since they know that if they guessed wrong, it will not haunt them for years.

You May Also Like